Berber languages

| Berber

Tamazight

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: |

North Africa (mainly Morocco and Algeria; smaller Berber communities in Burkina Faso, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Niger,and Tunisia) and also in Belgium, Canada, France, Netherlands, Spain and United States | ||

| Linguistic Classification: | Afro-Asiatic Berber |

||

| Subdivisions: |

? Guanche

Zenaga

Eastern Berber group ?

Northern Berber group

Tuareg group

|

||

| ISO 639-2 and 639-5: | ber | ||

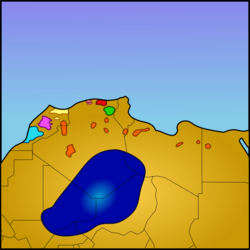

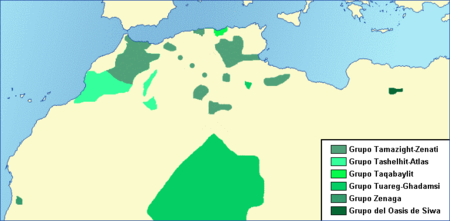

The pockets of Berber languages in modern-day North Africa

|

|||

The Berber languages (native name: Tamazight) are the indigenous languages of most of North Africa. The Berber group is a member of the Afroasiatic language family. A relatively sparse population speaking a group of very closely related and similar languages and dialects extends across the Atlas Mountains, the Sahara, and the northern part of the Sahel in Morocco, Algeria, Niger, Mali, Tunisia, Libya, and the Siwa Oasis area of Egypt. There is a movement among speakers of the closely related Northern Berber languages to unite them into a single standard language.

The name Tamazight, which traditionally referred specifically to Central Morocco Tamazight, and is also used by the native speakers of Riff (Tarifit), is being increasingly used for this Standard Berber, or even for Berber as a whole. Its usage is less consistent in some areas like the Kabylia where locals call their language Taqbaylit rather than Tamazight. Due to the rising Berber cultural and political activism and its recent prominence in the North African media, the popularity of the term Tamazight made it known and recognizable by virtually every citizen in North Africa, including non-Berber speakers.

Among the notable varieties of Berber are Central Morocco Tamazight, Riff, Shilha (Tashelhiyt), Kabyle (Taqbaylit), and the Tuareg dialect chain. The Berber languages have had a written tradition, on and off, for over 2,000 years, although the tradition has been frequently disrupted by various invasions. It was first written in the Tifinagh alphabet, still used by the Tuareg; the oldest dated inscription is from about 200 BC. Later, between about 1000 AD and 1500 AD, it was written in the Arabic alphabet; since the 20th century, it has often been written in the Latin alphabet, especially among the Kabyle.

A modernized form of the Tifinagh alphabet was made official in Morocco in 2003, and a similar one is sparsely used Algeria. The Berber Latin alphabet is preferred by Moroccan Berber writers and is still predominant in Algeria (although unofficially). Mali and Niger recognized the Berber Latin alphabet and customized it to the Tuareg phonological system. However, traditional Tifinagh is still used in those countries. Both Tifinagh and Latin scripts are being increasingly used in Morocco and parts of Algeria, while the Arabic script has been abandoned by Berber writers.

Contents |

Nomenclature

The term Berber has been used in Europe since at least the 17th century, and is still used today. It was borrowed from the Arabic designation for these populations, البربر, el-Barbar. The latter might have been derived from the Arabic or Persian words "barbakh"/"barbar" and "khanah", a house or guard on the wall. Although the Berbers obviously fell under that definition, Romans usually called them under more specific names, such as "Numidians" or "Mauri". The Egyptians referred to them as Rebu (= Libu), or Meshwesh, the ancient Greeks as "Libyans", the Byzantines as "Mazikes".

As far as languages are concerned, the term Tamazight has recently gained ground over Berber, particularly to refer to Northern Berber languages, just as "Amazigh" is used to refer to a native Berber speaker. It traditionally referred specifically to the Central Morocco Tamazight dialect. Etymologically, it means "language of the free" or "of the noblemen". Traditionally, the term "tamazight" (in various forms: "thamazighth", "tamasheq", "tamajeq", "tamahaq") was used by many Berber groups to refer to the language they spoke, including the Middle Atlas, the Rif, Sened in Tunisia, and the Tuareg. However, other terms were used by other groups; for instance, many parts of western Algeria called their language "taznatit" or Zenati, while the Kabyles called theirs "thaqvaylith", the inhabitants of Siwa "tasiwit", and the Zenaga. In Tunisia, the local Berber languages are usually referred to as "Shelha". ?? "Tuddhungiya".[1] Around the turn of the century, it was reported that the Zenata of the Rif called their language "Zenatia" specifically to distinguish it from the "Tamazight" spoken by the rest of the Rif.

One group, the Linguasphere Observatory, has attempted to introduce the neologism "Tamazic languages" to refer to the Berber languages.

Origin

Berber is a member of the Afroasiatic language family (formerly called Hamito-Semitic), along with such languages as Ancient Egyptian, Arabic, Hebrew, Hausa, and Somali. Berber has been present in the area since the first written accounts.[2].

The scripts of the languages, Tifinagh, are of Punic origin. Some think that Tifinagh might be of Berber origin.

Status

After independence, all the Maghreb countries to varying degrees pursued a policy of Arabization, aimed partly at displacing French from its colonial position as the dominant language of education and literacy. But under this policy the use of Amazigh / Berber languages has been suppressed or even banned. This state of affairs has been contested by Berbers in Morocco and Algeria — especially Kabylie — and is now being addressed in both countries by introducing Berber language in some schools and by recognizing Berber as a "national language" in Algeria,[3] though not an official one. No such measures have been taken in the other Maghreb countries. In Mali and Niger, there are a few schools that teach partially in Tamasheq.

Population

The exact population of Berber speakers is hard to ascertain, since most North African countries do not record language data in their censuses. The Ethnologue provides a useful academic starting point; however, its bibliographic references are inadequate, and it rates its own accuracy at only B-C for the area. Early colonial censuses may provide better documented figures for some countries; however, these are also very much out of date.

- "Few census figures are available; all countries (Algeria and Morocco included) do not count Berber languages. The 1972 Niger census reported Tuareg, with other languages, at 127,000 speakers. Population shifts in location and number, effects of urbanization and education in other languages, etc., make estimates difficult. In 1952 A. Basset (LLB.4) estimated the number of Berberophones at 5,500,000. Between 1968 and 1978 estimates ranged from eight to thirteen million (as reported by Galand, LELB 56, pp. 107, 123-25); Voegelin and Voegelin (1977, p. 297) call eight million a conservative estimate. In 2006, S. Chaker estimated that the Berberophone populations of Kabylie and the three Moroccan groups numbered more than one million each; and that in Algeria, 12,650,000, or one out of three Algerians, speak a Berber language (Chaker 1984, pp. 8-9)."[4]

- Morocco: In 1952, André Basset ("La langue berbère", Handbook of African Languages, Part I, Oxford) estimated that a "small majority" of Morocco's population spoke Berber. The 1960 census estimated that 34% of Moroccans spoke Berber, including bi-, tri-, and quadrilinguals. In 2000, Karl Prasse cited "more than half" in an interview conducted by Brahim Karada at Tawalt.com. According to the Ethnologue (by deduction from its Moroccan Arabic figures), the Berber-speaking population should be estimated at 35% or around 10.5 million speakers[5]. However, the figures it gives for individual languages only add up to 7.5 million, divided into three dialects:

A survey included in the official Moroccan census of 2004 and published by several Moroccan newspapers gave the following figures: 34% of people in rural regions spoke a Berber language and 21% in urban zones did, the national average would be 28.4% or 8.52 million[11]. It is possible, however, that the survey asked for the language "used in daily life" [12] which would result of course in figures clearly lower than those of native speakers, as the language is not recognized for official purposes and many Berbers who live in an Arabic-speaking environment cannot use it in daily life; also the use of Berber in public was frowned upon until the 1990s and might affect the result of the survey.

Adding up the population (according to the official census of 2004) of the Berber-speaking regions as shown on a 1973 map of the CIA results in at least 10 million speakers, not counting the numerous Berber population which lives outside these regions in the bigger cities.

Mohamed Chafik claims 80% of Moroccans are Berbers. It is not clear, however, whether he means "speakers of Berber languages" or "people of Berber descent".

The division of Moroccan Berber dialects in three groups, as used by The Ethnologue is common in linguistic publications, but is significantly complicated by local usage: thus Shilha is sub-divided into Shilha of the Dra valley, Tasusit (the language of the Souss) and several other (mountain)-dialects. Moreover, linguistic boundaries are blurred, such that certain dialects cannot accurately be described as either Central Morocco Tamazight (spoken in the Central and eastern Atlas area) or Shilha.

- Algeria: In 1906, the total population speaking Berber languages in Algeria (excluding the thinly populated Sahara) was estimated at 1,305,730 out of 4,447,149, i.e. 29%. (Doutté & Gautier, Enquête sur la dispersion de la langue berbère en Algérie, faite par l'ordre de M. le Gouverneur Général, Alger 1913.) The 1911 census, however, found 1,084,702 speakers out of 4,740,526, i.e. 23%; Doutté & Gautier suggest that this was the result of a serious undercounting of Shawiya in areas of widespread bilingualism. A trend was noted for Berber groups surrounded by Arabic (as in Blida) to adopt Arabic, while Arabic speakers surrounded by Berber (as in Sikh ou Meddour near Tizi-Ouzou) tended to adopt Berber. In 1952, André Basset estimated that about a third of Algeria's population spoke Berber. The Algerian census of 1966 found 2,297,997 out of 12,096,347 Algerians, or 19%, to speak "Berber." In 1980, Salem Chaker estimated that "in Algeria, 3,650,000, or one out of five Algerians, speak a Berber language" (Chaker 1984, pp. 8–9). According to the Ethnologue [1], more recent estimates include 14% (corresponding to the total figures it gives for each Berber language added together, 4 million) and (by deduction from its Algerian Arabic figures) 29% (Hunter 1996). Most of these are accounted for by two dialects (percentages based on historical population data from appropriate dates [2]):

- Kabyle: 2,540,000 = 9% (Ethnologue, 1995) - 6,000,000 = 20% (Ethnologue, 1998). Total for all countries (Ethnologue): 3,126,000. (Needless to say, the latter two figures, though cited by the same source, are mutually contradictory.) Mainly in Algiers, Bejaia, Tizi-Ouzou, Setif and Boumerdes.

- Shawiya: 1.4 million (Ethnologue, 1993), equivalent to 5% of the population. Mainly in Batna, Khenchela, Sétif, Souk Ahras, Oum-El-Bouaghi, Tebessa.

- A third group, despite a very small population, accounts for most of the area speaking Berber:

- Tuareg 25,000 in Algeria (Ethnologue, 1987), mainly in the Ahaggar mountains of the Sahara. Most Tuareg live in Mali and Niger (see below).

- Tunisia: Basset (1952) estimated about 1%, as did Penchoen (1968). According to the Ethnologue, there are only 26,000 speakers (1998) of a Berber language it calls "Djerbi" , but which Tunisians call "Shelha", in Tunisia, all in the south around Djerba and Matmata. The more northerly enclave of Sened apparently no longer speaks Berber. This would make 0.3% of the population.

- Libya: According to the Ethnologue (by deduction from its combined Libyan Arabic and Egyptian Arabic figures) the non-Arabic-speaking population, most of which would be Berber, is estimated at 4% (1991, 1996). However, the individual language figures it gives add up to 162,000, i.e. about 3%. This is mostly accounted for by languages:

- Nafusi language in Zuwarah and Jabal Nafusa: 141,000 (1998).

- Tahaggart Tuareg of Ghat: 17,000 (Johnstone 1993).

- Egypt: The oasis of Siwa near the Libyan border speaks a Berber language; according to the Ethnologue, there are 5,000 speakers there (1995). Its population in 1907 was 3884 (according to the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica); the claimed lack of increase seems surprising.

- Mauritania: According to the Ethnologue, only 200-300 speakers of Zenaga remain (1998). It also mentions Tamasheq, but does not provide a population figure for it. Most non-Arabic speakers in Mauritania speak Niger-Congo languages.

- Mali: The Ethnologue counts 440,000 Tuareg (1991) speaking:

-

- Tamasheq: 250,000

- Tamajaq: 190,000

-

- Tawallamat Tamajaq: 450,000

- Tayart Tamajeq: 250,000

- Tamahaq language: 20,000

- Burkina Faso: The Ethnologue counts 20,000 - 30,000 Tuareg (SIL 1991), speaking Kidal Tamasheq. However the Ethnologue is very inaccurate here appearing to miss the largest group of Tamasheq in Burkina in the province of Oudalan. The Tamasheq speaking population of Burkina is nearer to 100,000 (2005), with around 70,000 Tamasheq speakers in the province of Oudalan, the rest mainly in Seno, Soum, Yagha, Yatenga and Kadiogo provinces. About 10% of Burkina Tamasheq speak a version of the Tawallamat dialect.

- Nigeria: The Ethnologue notes the presence of "few" Tuareg, speaking Tawallamat Tamajaq.

- France: The Ethnologue lists 537,000 speakers for Kabyle, 150,000 for Central Morocco Tamazight, and no figures for Shilha or Riff. For the rest of Europe, it has no figures.

- Spain: A majority of Melilla's 80,000 inhabitants, and a minority of Ceuta's inhabitants, speak Berber.[13]

- Israel: Around two thousand mostly elderly Moroccan-born Israelis of Berber Jewish descent use Judeo-Berber dialects (as opposed to Moroccan Jews who trace descent from Spanish-speaking Sephardi Jews expelled from Spain, or Arabic-speaking Moroccan Jews).

Thus, judging by the not necessarily reliable Ethnologue, the total number of speakers of Berber languages in the Maghreb proper appears to lie anywhere between 16 and 25 million, depending on which estimate is accepted; if we take Basset's estimate, it could be as high as 30 million. The vast majority are concentrated in Morocco and Algeria. The Tuareg of the Sahel add another million or so.

Grammar

Nouns in the Berber languages vary in gender (masculine vs. feminine), in number (singular vs. plural) and in state (free state vs. construct state). In the case of the masculine, nouns generally begin with one of the three vowels of Berber, a, u or i (in standardised orthography, e represents a schwa [ə] inserted for reasons of pronunciation):

-

- afus "hand"

- argaz "man"

- udem "face"

- ul "heart"

- ixef "head"

- iles "tongue"

While the masculine is unmarked, the feminine (also used to form diminutives and singulatives, like an ear of wheat) is marked with the circumfix t...t. Feminine plural takes a prefix t... :

-

- afus → tafust

- udem → tudemt

- ixef → tixeft

- ifassen → tifassin

Berber languages have two types of number: singular and plural, of which only the latter is marked. Plural has three forms according to the type of nouns. The first, "regular" type is known as the "external plural"; it consists in changing the initial vowel of the noun, and adding a suffix -n:

-

- afus → ifassen "hands"

- argaz → irgazen "men"

- ixef → ixfawen "heads"

- ul → ulawen "hearts"

The second form of the plural is known as the "broken plural". It involves only a change in the vowels of the word:

-

- adrar → idurar "mountain"

- agadir → igudar "wall / castle"

- abaghus → ibughas "monkey"

The third type of plural is a mixed form: it combines a change of vowels with the suffix -n:

-

- izi → izan "(the) fly"

- azur → izuran "root"

- iziker → izakaren "rope"

Berber languages also have two types of states or cases of the noun, organized ergatively: one is unmarked, while the other serves for the subject of a transitive verb and the object of a preposition, among other contexts. The former is often called free state, the latter construct state. The construct state of the noun derives from the free state through one of the following rules: The first involves a vowel alternation, whereby the vowel a becomes u :

-

- argaz → urgaz

- amghar → umghar

- adrar → udrar

The second involves the loss of the initial vowel, in the case of some feminine nouns:

-

- tamghart → temghart "woman / mature woman"

- tamdint → temdint "town"

- tarbat → terbat "girl"

The third involves the addition of a semi-vowel (w or y) word-initially:

-

- asif → wasif "river"

- aḍu → waḍu "wind"

- iles → yiles "tongue"

- uccen → wuccen "wolf"

Finally, some nouns do not change for free state:

-

- taddart → taddart "house / village"

- tuccent → tuccent "female wolf"

The following table gives the forms for the noun amghar "old man / leader":

| masculine | feminine | |||

| default | agent | default | agent | |

| singular | amghar | umghar | tamghart | temghart |

| plural | imgharen | yimgharen | timgharin | temgharin |

Subclassification

Subclassification of the Berber languages is made difficult by their mutual closeness; Maarten Kossmann (1999) describes it as two dialect continua, Northern Berber and Tuareg, and a few peripheral languages, spoken in isolated pockets largely surrounded by Arabic, that fall outside these continua, namely Zenaga and the Libyan and Egyptian varieties. Within Northern Berber, however, he recognizes a break in the continuum between Zenati languages and their non-Zenati neighbors; and in the east, he recognizes a division between Ghadames and Awjila on the one hand and Sokna (Al Fuqahā'), Siwa, and Djebel Nefusa on the other. The implied tree is:

- Nafusi-Siwi languages (including Sokna)

- Ghadames-Awjila languages

- Northern Berber languages

- Zenati languages (including Riff)

- Kabyle language

- Atlas languages

- Tuareg languages

- Zenaga language

There is so little data available on Guanche that any classification is necessarily uncertain; however, it is almost universally acknowledged as Afro-Asiatic on the basis of the surviving glosses, and widely suspected to be Berber. Much the same can be said of the language, sometimes called "Numidian", used in the Libyan or Libyco-Berber inscriptions around the turn of the Common Era, whose alphabet is the ancestor of Tifinagh.

The Ethnologue, mostly following Aikhenvald and Militarev (1991), treats the eastern varieties differently:

- Guanche

- Eastern Berber languages

- Siwi

- Awjila-Sokna languages

- Northern Berber languages

- Zenati (including Riff, Nafusi, and Ghadames)

- Kabyle language

- Chenoua language

- Atlas languages

- Tuareg languages

- Zenaga language

Influence on other languages

Berber languages have influenced Maghrib Arabic dialects, such as Moroccan Arabic or Maltese, as the substratum. They also have influenced Iberian Romance languages due to the Muslim rule of the Iberian peninsula in the Middle Ages. Their influence is also seen in some languages in subsaharan Africa.

See also

- Arsène Roux

- Michael Peyron

- Karl Prasse

- Henri Basset

- Tifinagh

- Berber alphabet

- Berber Latin alphabet

- Numidians

- Kabyle

- Rif

- Tuareg

Notes

- ↑ http://www.rosettaproject.org/live/search/showpages?ethnocode=ZEN&doctype=detail&version=0&scale=six

- ↑ BERBER, A “LONG-FORGOTTEN” LANGUAGE OF FRANCEPDF (187 KB), p. 1.

- ↑ (French) - « Loi n° 02-03 portent révision constitutionnelle », adopted on April 10, 2002, allotting in particular to "Tamazight" the status of national language.

- ↑ http://www.isp.msu.edu/AfrLang/Berber-root.html

- ↑ The Ethnologe, Languages of Morocco

- ↑ The Ethnologue

- ↑ The Ethnologue

- ↑ The Ethnologue

- ↑ INALCO

- ↑ INALCO

- ↑ Bladinet

- ↑ Al Bayane Newspaper, 10/07/2005

- ↑ http://www.uoc.edu/euromosaic/web/document/berber/an/i1/i1.html#1

References

- Ethnologue entry for Berber languages

- Brett, Michael; & Fentress, Elizabeth (1997). The Berbers (The Peoples of Africa). ISBN 0-631-16852-4. ISBN 0-631-20767-8 (Pbk).

- Abdel-Massih, Ernest T. 1971. A Reference Grammar of Tamazight (Middle Atlas Berber). Ann Arbor: Center for Near Eastern and North African Studies, The University of Michigan

- Basset, André. 1952. La langue berbère. Handbook of African Languages 1, ser. ed. Daryll Forde. London: Oxford University Press

- Chaker, Salem. 1995. Linguistique berbère: Études de syntaxe et de diachronie. M. S.—Ussun amaziɣ 8, ser. ed. Salem Chaker. Paris and Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters

- Dallet, Jean-Marie. 1982. Dictionnaire kabyle–français, parler des At Mangellet, Algérie. Études etholinguistiques Maghreb–Sahara 1, ser. eds. Salem Chaker, and Marceau Gast. Paris: Société d’études linguistiques et anthropologiques de France

- de Foucauld, Charles Eugène. 1951. Dictionnaire touareg–français, dialecte de l’Ahaggar. 4 vols. [Paris]: Imprimerie nationale de France

- Delheure, Jean. 1984. Aǧraw n yiwalen: tumẓabt t-tfransist, Dictionnaire mozabite–français, langue berbère parlée du Mzab, Sahara septentrional, Algérie. Études etholinguistiques Maghreb–Sahara 2, ser. eds. Salem Chaker, and Marceau Gast. Paris: Société d’études linguistiques et anthropologiques de France

- ———. 1987. Agerraw n iwalen: teggargrent–taṛumit, Dictionnaire ouargli–français, langue parlée à Oaurgla et Ngoussa, oasis du Sahara septentrinal, Algérie. Études etholinguistiques Maghreb–Sahara 5, ser. eds. Salem Chaker, and Marceau Gast. Paris: Société d’études linguistiques et anthropologiques de France

- Kossmann, Maarten G. 1999. Essai sur la phonologie du proto-berbère. Grammatische Analysen afrikaniscker Sprachen 12, ser. eds. Wilhelm J. G. Möhlig, and Bernd Heine. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag

- Kossmann, Maarten G., and Hendrikus Joseph Stroomer. 1997. "Berber Phonology". In Phonologies of Asia and Africa (Including the Caucasus), edited by Alan S. Kaye. 2 vols. Vol. 1. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. 461–475

- Naït-Zerrad, Kamal. 1998. Dictionarrie des racines berbères (formes attestées). Paris and Leuven: Centre de Recherche Berbère and Uitgeverij Peeters

- Prasse, Karl-Gottfried, Ghubăyd ăgg-Ălăwžəli, and Ghăbdəwan əg-Muxămmăd. 1998. Asăggălalaf: Tămaẓəq–Tăfrăsist — Lexique touareg–français. 2nd ed. Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications 24, ser. eds. Paul John Frandsen, Daniel T. Potts, and Aage Westenholz. København: Museum Tusculanum Press

- Quitout, Michel. 1997. Grammaire berbère (rifain, tamazight, chleuh, kabyle). Paris and Montréal: Éditions l’Harmattan

- Rössler, Otto. 1958. "Die Sprache Numidiens". In Sybaris: Festschrift Hans Krahe zum 60. Geburtstag am 7. February 1958, dargebracht von Freunden, Schülern und Kollegen. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz

- Sadiqi, Fatima. 1997. Grammaire du berbère. Paris and Montréal: Éditions l’Harmattan. ISBN 2-7384-5919-6

- Cannon, Garland. 1994. The Arabic Contributions to the English Language: A Historical Dictionary.

External links

- The Tamazight Language Profile

- Etymolgy of "Berber"

- Etymology of "Amazigh"

- Early Christian history of Berbers

- (French)(Berber)Tawiza Amazigh Monthly newspaper

- Amuddu n-Umsiggel - a philosophical Berber story

- Interview with Karl-G. Prasse (source)

- Libyamazigh Page about Libyan culture with a Berber language section.

- Tifinagh

- Ancient Scripts

- Ennedi

- Berber

- Interview with Rachid Aadnani on the Amazigh issue

- Algerian Dardja Online Dictionary: contains many Berber terms

- Imyura Kabyle site about literature

French

- (French)Berber Research Center (INALCO, Paris) Articles and maps of high scientific value for a large audience

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||